Algebraic function

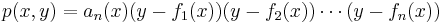

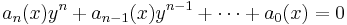

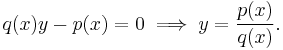

In mathematics, an algebraic function is informally a function that satisfies a polynomial equation whose coefficients are themselves polynomials with rational coefficients. For example, an algebraic function in one variable x is a solution y for an equation

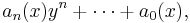

where the coefficients ai(x) are polynomial functions of x with rational coefficients. A function which is not algebraic is called a transcendental function.

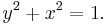

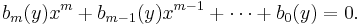

In more precise terms, an algebraic function may not be a function at all, at least not in the conventional sense. Consider for example the equation of a circle:

This determines y, except only up to an overall sign:

However, both branches are thought of as belonging to the "function" determined by the polynomial equation. Thus an algebraic function is most naturally considered as a multiple valued function.

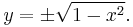

An algebraic function in n variables is similarly defined as a function y which solves a polynomial equation in n + 1 variables:

It is normally assumed that p should be an irreducible polynomial. The existence of an algebraic function is then guaranteed by the implicit function theorem.

Formally, an algebraic function in n variables over the field K is an element of the algebraic closure of the field of rational functions K(x1,...,xn). In order to understand algebraic functions as functions, it becomes necessary to introduce ideas relating to Riemann surfaces or more generally algebraic varieties, and sheaf theory.

Contents |

Algebraic functions in one variable

Introduction and overview

The informal definition of an algebraic function provides a number of clues about the properties of algebraic functions. To gain an intuitive understanding, it may be helpful to regard algebraic functions as functions which can be formed by the usual algebraic operations: addition, multiplication, division, and taking an nth root. Of course, this is something of an oversimplification; because of casus irreducibilis (and more generally the fundamental theorem of Galois theory), algebraic functions need not be expressible by radicals.

First, note that any polynomial is an algebraic function, since polynomials are simply the solutions for y of the equation

More generally, any rational function is algebraic, being the solution of

Moreover, the nth root of any polynomial is an algebraic function, solving the equation

Surprisingly, the inverse function of an algebraic function is an algebraic function. For supposing that y is a solution of

for each value of x, then x is also a solution of this equation for each value of y. Indeed, interchanging the roles of x and y and gathering terms,

Writing x as a function of y gives the inverse function, also an algebraic function.

However, not every function has an inverse. For example, y = x2 fails the horizontal line test: it fails to be one-to-one. The inverse is the algebraic "function"  . In this sense, algebraic functions are often not true functions at all, but instead are multiple valued functions.

. In this sense, algebraic functions are often not true functions at all, but instead are multiple valued functions.

Another way to understand this, which will become important later in the article, is that an algebraic function is the graph of an algebraic curve.

The role of complex numbers

From an algebraic perspective, complex numbers enter quite naturally into the study of algebraic functions. First of all, by the fundamental theorem of algebra, the complex numbers are an algebraically closed field. Hence any polynomial relation

- p(y, x) = 0

is guaranteed to have at least one solution (and in general a number of solutions not exceeding the degree of p in x) for y at each point x, provided we allow y to assume complex as well as real values. Thus, problems to do with the domain of an algebraic function can safely be minimized.

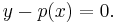

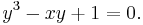

Furthermore, even if one is ultimately interested in real algebraic functions, there may be no adequate means to express the function in a simple manner without resorting to complex numbers (see casus irreducibilis). For example, consider the algebraic function determined by the equation

Using the cubic formula, one solution is (the red curve in the accompanying image)

There is no way to express this function in terms of real numbers only, even though the resulting function is real-valued on the domain of the graph shown.

On a more significant theoretical level, using complex numbers allow one to use the powerful techniques of complex analysis to discuss algebraic functions. In particular, the argument principle can be used to show that any algebraic function is in fact an analytic function, at least in the multiple-valued sense.

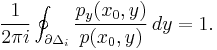

Formally, let p(x, y) be a complex polynomial in the complex variables x and y. Suppose that x0 ∈ C is such that the polynomial p(x0,y) of y has n distinct zeros. We shall show that the algebraic function is analytic in a neighborhood of x0. Choose a system of n non-overlapping discs Δi containing each of these zeros. Then by the argument principle

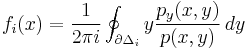

By continuity, this also holds for all x in a neighborhood of x0. In particular, p(x,y) has only one root in Δi, given by the residue theorem:

which is an analytic function.

Monodromy

Note that the foregoing proof of analyticity derived an expression for a system of n different function elements fi(x), provided that x is not a critical point of p(x, y). A critical point is a point where the number of distinct zeros is smaller than the degree of p, and this occurs only where the highest degree term of p vanishes, and where the discriminant vanishes. Hence there are only finitely many such points c1, ..., cm.

A close analysis of the properties of the function elements fi near the critical points can be used to show that the monodromy cover is ramified over the critical points (and possibly the point at infinity). Thus the entire function associated to the fi has at worst algebraic poles and ordinary algebraic branchings over the critical points.

Note that, away from the critical points, we have

since the fi are by definition the distinct zeros of p. The monodromy group acts by permuting the factors, and thus forms the monodromy representation of the Galois group of p. (The monodromy action on the universal covering space is related but different notion in the theory of Riemann surfaces.)

History

The ideas surrounding algebraic functions go back at least as far as René Descartes. The first discussion of algebraic functions appears to have been in Edward Waring's 1794 An Essay on the Principles of Human Knowledge in which he writes:

- let a quantity denoting the ordinate, be an algebraic function of the abscissa x, by the common methods of division and extraction of roots, reduce it into an infinite series ascending or descending according to the dimensions of x, and then find the integral of each of the resulting terms.

References

- Ahlfors, Lars (1979). Complex Analysis. McGraw Hill.

- van der Waerden, B.L. (1931). Modern Algebra, Volume II. Springer.

![y^n-p(x)=0 \implies y=\sqrt[n]{p(x)}.](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/0e6043dc7717cca9ba05d5567366478e.png)

![y=-\frac{(1%2Bi\sqrt{3})x}{2^{2/3}\sqrt[3]{729-108x^3}}-\frac{(1-i\sqrt{3})\sqrt[3]{-27%2B\sqrt{729-108x^3}}}{6\sqrt[3]{2}}.](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/3369bbe90a387b41bbe25214063abb56.png)